The Discount Is the Signal

In 2021, Plaid raised at a $13.4 billion valuation. By early 2025, secondary shares were changing hands at roughly $6.1 billion — a 55% discount.

Was Plaid broken? No. Revenue was growing. The product was embedded in thousands of fintech apps. The company was quietly positioning for an eventual IPO.

The discount wasn't telling investors Plaid was in trouble. It was telling them the 2021 round was priced in a different universe — one with zero interest rates, 50x revenue multiples, and a buyer willing to pay $13.4 billion for a company that hadn't yet grown into that number. The secondary market wasn't pessimistic about Plaid. It was realistic.

This is the part most people get wrong about discounts. A company raises at $10 billion. Six months later, you can buy shares on the secondary market at a price implying $7 billion. The natural reaction: great deal. Maybe. But maybe not.

Private markets don't have a ticker. No closing bell, no real-time order book. When secondary shares change hands, the transaction is bespoke, privately negotiated, and rarely disclosed. In public markets, a 30% drop means hundreds of thousands of participants have collectively repriced the asset. In private markets, it might mean one motivated seller met one cautious buyer on one particular Tuesday.

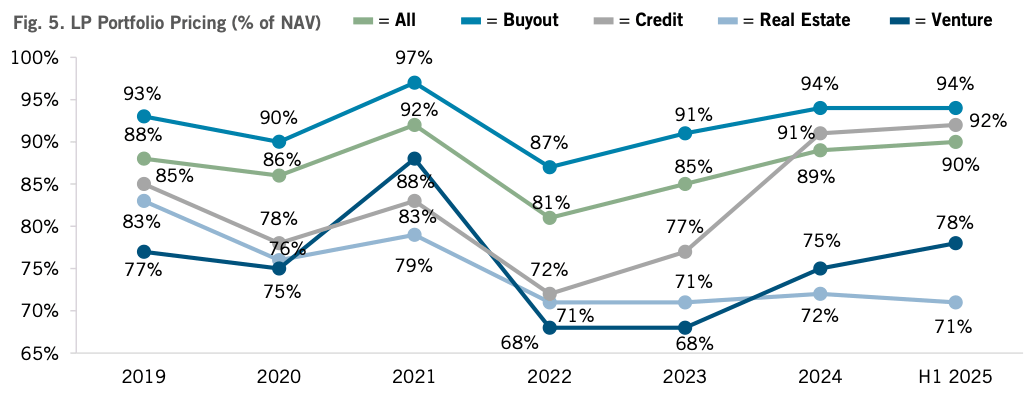

Venture and growth portfolios traded at roughly 78% of NAV in the first half of 2025, up from the high 60s in 2023, per Jefferies. The market is recovering, but discounts are still significant. The question isn't whether they exist. It's what they mean.

Here are five explanations — listed in the order experienced secondary investors evaluate them, not the order most people assume:

1. The last round was overpriced.

This is the one nobody wants to hear, but it's often the right answer. In 2020 and 2021, hundreds of companies raised at valuations that reflected peak-market optimism, near-zero interest rates, and FOMO-driven term sheets. When secondary shares trade at a discount to those marks, the market isn't saying the company is in trouble. It's saying the last round wasn't realistic.

The discount here isn't a bargain. It's a correction. Plaid is the textbook case, but it's far from the only one.

How to spot it: Look at the round vintage. If the last primary raise was in 2021 and the company hasn't raised since, the stated valuation may bear little relationship to current market conditions. Compare the implied revenue multiple at the last round to where public comparables trade today.

2. Someone needs liquidity — and that's all.

An early employee is buying a house. A VC fund is past its fund life and returning capital to LPs. A founder is diversifying after eight years of concentrated risk.

None of these sellers are making a statement about the company's prospects. They're solving a personal financial problem. But their urgency gets priced in. If you need to sell and there are only two buyers, you're probably not getting full value. The discount reflects the cost of liquidity, not a judgment about the business.

How to spot it: Employee sales during a transfer window, or a known fund winding down, suggest liquidity pressure rather than fundamental concern. If the company itself is running a structured tender offer, that's a different — and often more favorable — dynamic.

3. The market knows something you don't.

Private companies don't file quarterly reports. They don't host earnings calls. When an insider sells at a steep discount, they may be acting on information — slowing growth, a failed product launch, a key customer departure — that won't become public for months.

This is the information asymmetry problem that defines private markets. In public markets, material nonpublic information is tightly regulated. In private markets, it's the water everyone swims in.

How to spot it: You often can't — which is the point. But if multiple independent sellers are hitting the market at the same time for the same company, and there's no obvious liquidity event driving it, pay attention. Volume of sellers, not just price, is a signal.

4. Structural issues are getting priced.

Not all shares are created equal. Preferred shares from the last round carry liquidation preferences, anti-dilution protections, and sometimes guaranteed returns. When you buy secondary shares, you're often buying an inferior position in the capital structure at a price that reflects a headline valuation set by superior securities.

A 25% discount to the last round might actually be fair value once you account for the preference stack. You're not getting a deal. You're getting accurately priced.

How to spot it: Ask about the share class. Common shares should almost always trade at some discount to the latest preferred round — that's the capital structure working as designed, not a red flag.

5. The market is inefficient — and you're genuinely early.

Sometimes a discount really does represent opportunity. A company is executing well, revenue is growing, and the secondary market hasn't caught up because there simply aren't enough transactions to establish a new price. Or macro sentiment has dragged down all private market pricing regardless of individual company performance.

But here's the discipline: this should be your last explanation, not your first. Most investors start here. Experienced secondary market participants start with explanations one through four and work their way down.

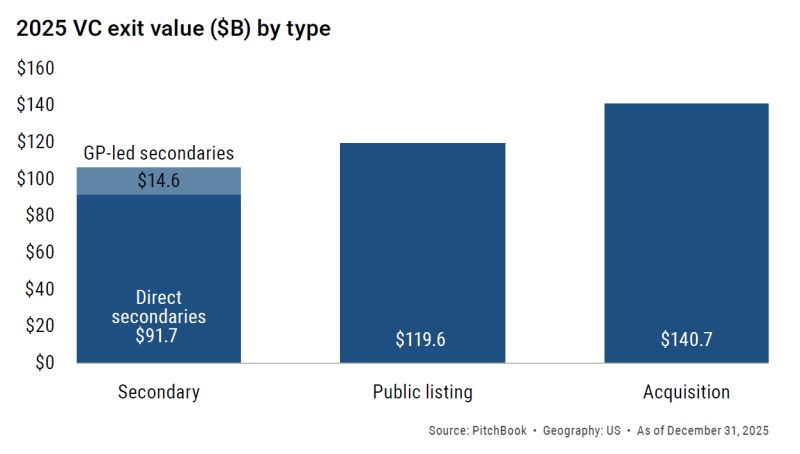

What the Data Says

The pricing dynamics across private market secondaries reinforce why blanket assumptions about discounts are dangerous. According to the Jefferies H1 2025 Global Secondary Market Review:

Asset Class

Avg. Price as % of NAV (H1 2025)

Buyout portfolios

94%

Credit portfolios

91%

Venture/growth portfolios

78%

Real estate portfolios

71%

These are LP-led portfolio transactions, not direct company share sales — but the hierarchy is instructive. Buyout assets with proven cash flows and clear exit paths trade near par. Venture and growth assets, where valuations are more speculative and outcomes more binary, carry wider discounts. Real estate, still weighed down by elevated rates and slow refinancing, trades at the steepest discounts.

The discount isn't random. It reflects a judgment about uncertainty.

For individual company shares, the range is even wider. Pre-IPO names with strong fundamentals, clear IPO timelines, and regular tender offers trade at or near their last round price. Others — particularly companies with stale 2021-era marks or uncertain revenue trajectories — can trade at 40-60% discounts.

The Checklist

Before evaluating any secondary opportunity, ask these five questions:

When was the last primary round? If it was more than 18 months ago, the stated valuation may not reflect current conditions. The discount might just be the market catching up.

Who is selling, and why? A founder selling 5% of their holdings during a structured tender is very different from a VC dumping shares on a platform. Seller motivation matters enormously.

What share class are you buying? Common shares should trade at a discount to preferred. That's not a buying opportunity — it's the capital structure functioning normally.

Are public comparables up or down? If the entire SaaS sector has repriced 30% lower in public markets, private valuations haven't adjusted yet. What looks like a company-specific discount may actually be a sector-wide repricing that hasn't fully flowed through.

Is the company facilitating secondary transactions? Companies that run regular tender offers — SpaceX is the clearest example, with its bi-annual programs — typically see tighter pricing and more orderly markets. Companies that block transfers or aggressively exercise ROFR tend to have wider spreads and less reliable price discovery.

Why This Matters Right Now

The secondary market is entering an unusual period. Several of the largest private companies in history — SpaceX, OpenAI, Anthropic — may pursue IPOs over the next 12-18 months. When they do, secondary prices will converge with public market valuations in real time.

For investors holding secondary shares, the gap between what they paid and what the public market says those shares are worth will become immediately visible. Some discounts will prove to have been genuine bargains. Others will prove to have been accurate pricing of real risks that didn't go away just because the company went public.

Quick Takes

Some interesting raises from the past few days:

Apptronik raises $520M, tripling its valuation to $5.5B — The humanoid robotics startup's Series A extension brings total round to $935M. Google and Mercedes-Benz backed the deal. Worth noting: investors paid 3x the original Series A price for the extension shares — the opposite of a discount, and a signal of its own.

Inertia Enterprises secures $450M Series A for laser-driven fusion — Co-founded by Twilio CEO Jeff Lawson, the startup is building laser systems for grid-scale fusion power. One of the largest Series A rounds in the energy sector.

Skyryse raises $300M+ Series C for aviation automation — The simplified flight controls company is targeting commercial aviation applications with its latest round..

📊 Data Point of the Day

78%

Average price as a percentage of NAV for venture and growth secondary portfolios in H1 2025 — up from 68% in 2023, but still well below the 94% that buyout portfolios command. The gap reflects the fundamental uncertainty premium embedded in earlier-stage, higher-growth assets.

🎓 Manual

Discount for Lack of Marketability (DLOM)

A reduction in value applied to private company shares to account for the fact that they can't be easily sold on a public exchange. Typically estimated at 20-30% relative to comparable public companies, DLOM is one reason private shares generally trade below what public market multiples might suggest — and why a "discount" to last round doesn't always mean you're getting a deal.

FOR ACCREDITED INVESTORS ONLY: Under federal securities laws, private market investments on this platform are available exclusively to Accredited Investors. Verification of status required before investing. Private investments involve significant risks including illiquidity, potential loss of principal, and limited disclosure requirements. "Augment" refers to Augment Markets, Inc. and its affiliates. Augment Markets, Inc. is a technology company offering software and data services. Investment advisory services are offered through Augment Advisors, LLC, an SEC-registered investment adviser. Brokerage services are offered through Augment Capital, LLC, an affiliated broker-dealer and member FINRA/SIPC. Registration with the SEC does not imply a certain level of skill or training. Neither Augment Advisors, LLC nor Augment Capital, LLC provide legal or tax advice; consult your attorney or tax professional regarding your specific situation. For additional information, please refer to Augment Advisors, LLC’s Form ADV Part 2A (Firm Brochure) and FINRA BrokerCheck.